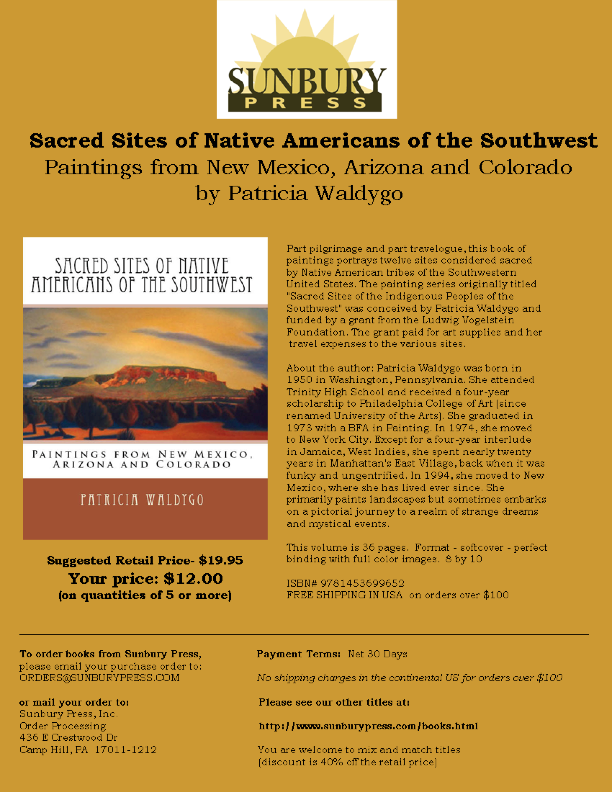

Sacred Sites of Native Americans of the Southwest

by Patricia Waldygo

- Home

- Hot Off the Presses!

- Free Sample Edit, Fees

- The Many Ways a Book Can Go Wrong

- Proofreading – Copy Editing – Line Editing

- What Do Book Publishers Want?

- Should I Self-Publish?

- The Editing Process

- Tips on Editing Fiction

- Become a Freelance Book Editor

- Proper Manuscript Format

- Sacred Sites Book by PNW

- Magazine Articles Written by PN Waldygo

- Fiction Written by PNW

- Contact Desert Sage

(WRITING SAMPLE, NONFICTION)

In 2010, Sunbury Press published a small book of my paintings. I am both the author of the book and the artist. (The book can be purchased on Amazon.com.) Scroll down for excerpts.

—P. N. WALDYGO

Excerpts from the book:

SACRED SITES OF NATIVE AMERICANS OF THE SOUTHWEST

(A painting series funded by the Ludwig Vogelstein Foundation)

Introduction

Mountains are the homes of our gods, rock formations our shrines.

—Conroy Chino, former TV news anchor (1)

and New Mexico Secretary of Labor

In 1997, I embarked on a journey to do a series of paintings of “Sacred Sites of the Indigenous Peoples of the Southwest.” The original plan was to visit and paint little-known, remote sacred Native American sites. Before long, I came to realize this was a bad idea.

When I first conceived of the project, I was motivated by curiosity and a sense of adventure. These sites had traditionally been considered sacred for hundreds, even thousands, of years, so I figured there must be a good reason—possibly based on the same esoteric principles of geomancy as in Chinese and Tibetan feng shui. In those systems, there are certain locations on earth where the energies of earth, wind, and water combine harmoniously to create a confluence of balanced forces—an energetically uplifting “power spot.”

Whether or not this was true for the sites I chose, my thinking was flawed. First,

"The point is, as noted by the native worldview, all of Mother Earth is sacred, not just archaeological and historical sites or traditional cultural places. [According to one] tribal cultural specialist . . . , 'How can I say over here is important and over here is important, but in between is not. It is all important. That is like asking me which part of my body is less important so you can cut it off. My fingers? My toes? My breast? My head?'" (Stapp and Burney, Tribal Cultural Resource Management) (2)

Nevertheless, as Leon Skyhorse Thomas of Chinle, Arizona, admitted to me, some sites are more sacred than others.

These may include

"vision questing sites; sweat bath sites; monumental geological features; ritually modified areas or rock art sites; burial areas and cemeteries; boundaries between cultural, life, and geological zones; mountain passes; headwaters of streams and rivers; confluences of rivers; cascades, waterfalls, rapids, hot and cold springs; caves; gathering areas where sacred plants, stones, and other cultural materials are available; sites of historical significance; hills; lakes; rivers; islands; cairns; and other rock alignments." (Stapp and Burney, Tribal Cultural Resource Management) (3)

An even worse flaw in my plan is that I soon realized that by publicizing these sites, I would do Native Americans a disservice. They are trying to protect the sites and keep them private, but my paintings might create more interest in them and could tempt tourists or adventurers to trespass in restricted areas.

I saw that I was motivated by the same tendencies that Anglos have displayed throughout history. I came across the following comment:

"It’s non-Indians, primarily archaeologists and anthropologists, who want to identify, catalog, record, photograph, and, whenever possible, publish their findings. (4)

. . . But the Wanapum have other reasons for holding their history close. They don’t lightly share the stories that form their cultural heritage. “You don’t say a lot. Then you say a little more. Pretty soon someone wants to write a book,” Buck said." (Stapp and Burney, Tribal Cultural Resource Management) (5)

After a while, I revised my original list of sites to include only those that can be seen from a distance, without trespassing on sacred ground; those that are now on public land or in areas owned by various tribes that have decided to permit visitors; and sites that are generally known to the public.

1. Conroy Chino, of the Acoma Tribe, had a 24-year career in television news and was New Mexico's Secretary of Labor under Governor Bill Richardson from 2002 to 2006. Quote taken from "The Back Page," New Mexico Journey (published by AAA), March/April 1998.

2. Darby C. Stapp and Michael S. Burney, Tribal Cultural Resource Management, Heritage Resources Management Series, vol. 4 (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, 2002), p. 155.

3. Stapp and Burney, Tribal Cultural Resource Management, pp. 156-157.

4. Ibid., p. 158.

5. Ibid., p. 133.

Mount Taylor

“By auspicious coincidence, I once edited a book by the late Paula Gunn Allen, a renowned writer and a UCLA English professor who hailed from Laguna Pueblo. During a phone conversation, she mentioned that Mount Taylor is considered a feminine mountain by Native Americans, yet Anglos had given it a male name, after U.S. president Zachary Taylor. I used delicate colors of gold, rose, and lavender to paint Mount Taylor, in order to evoke a feminine essence, overcome its masculine name, and reflect its Native American heritage.”

Mount Taylor, near Grants, New Mexico, is the Navajo’s Sacred Mountain of the South. Known as Tso odzil, “Turquoise Mountain,” it is “fastened to earth with a stone knife and covered with a blue sky blanket decorated with turquoise, white corn, dark mists and female rain.”(13)

The Anasazi, whom the Navajo call “the Ancient Ones,” regarded Mount Taylor as sacred and performed religious rituals high on its slopes.(14) Mount Taylor is sacred to members of the Laguna Pueblo tribe as well. They call it Tse’-pina/Kaweshtima (“The Woman Veiled in Clouds”).

Uranium mining took place all around Mount Taylor. The Jackpile Mine was the foremost supplier of “yellowcake” to the world for many years.

Regarding the bomb detonated at Stallion Gate, seventy miles southeast of Laguna, Paula Gunn Allen wrote,

"It was sunrise that day, July 16, 1945, a sunrise that came earlier than the rising sun itself. It was the day the 4th world ended and the 5th began. That was the time one of Old Spider’s sister-nieces came home. Her name was Sun Woman, and she had long ago gone away, heading east, but they always said she would come back and I guess that July in 1945 she did. Anyway, that’s what they say."(15)

13. See "Turquoise Mountain," http://thssite.tripod.com/shell/turq.html, accessed July 5, 2010.

14. See "Timeless Heritage: A History of Forest Service in the Southwest," at www.fs.fed.us/r3/about/history/timeless/th_shell.php?list=2, accessed July 5, 2010.

15. Paula Gunn Allen, Off the Reservation: Reflections on Boundary-Busting, Border-Crossing Loose Canons (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998), pp. 236-237).